Updated 5-4-23

Socrates debating his method of inquiry

How You Can Use the Socratic Method to Solve Problems

In this follow up to the article “How You Can Change the Future Part 1” I would like to provide a simple example to illustrate how applying the Socratic Method to reviewing a problem can help break it down to its essential components, isolate the potential problem areas and then help uncover the best options for dealing with it.

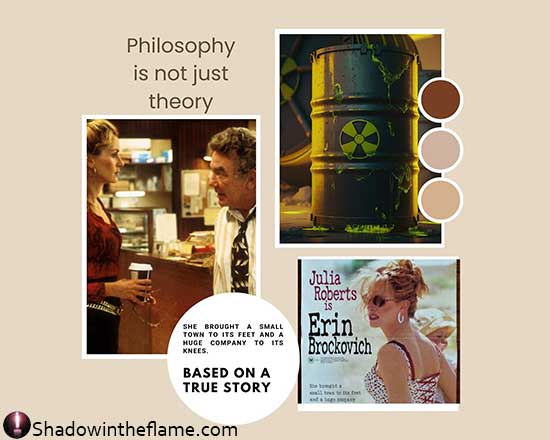

One example described in part 1 of this article was of living near an industrial plant or on the site of an old industrial plant that may have been polluted but has been sold to people to build a home. What do you do if you think there is a high incidence of illness in the area and suspect this may be because of pollution from the industrial plant? Here are some questions Socrates might consider;

- Do you accept that the site or nearby industrial plant is safe because the plant owner / property developer, or the local government, declares it to be safe?

- If the community accepts these assurances should you question it?

- Do you take it upon yourself to check this fact?

- How do you go about checking it?

It should be understood that while I am using a specific example to illustrate the method, the principle of asking the right questions applies to any problem you wish to address.

After you have determined what questions you need to ask, you may have questions about the questions, for example:

- If you ring the plant manager and ask are they polluting the air, the water or the soil, do you believe if they were, they would admit it to you because you ask them?

- Would a developer admit that the block of land he sold you is unsafe if it meant incurring an enormous cost to properly clean up the site?

- Finally, considering that you don’t know for sure if there is a problem, do you run the risk of being considered a troublemaker for asking these troublesome questions and making yourself unpopular?

What would Socrates Do?

If you don’t want to run away from the issue but recognise that you alone cannot solve the problem, your first course of action should be to concentrate on convincing the community that it cannot harm them to “investigate” the relevant questions but it may harm them if they don’t.

Help the community recognise there may be a problem by asking questions.

Asking questions is a skill that can be learned. Do you remember as a teenager you may have got home very late and standing just inside the door as you sneak in, is an irate father or mother whose burning question is “Where have you been and why are you so late?” Often followed up with “Have you been drinking?” or worse “You are drunk, look at yourself, you should be ashamed”

These may be very relevant questions, but are they framed in the best way to get a reasonable response or did they just put your back up and cause an argument?

Surely, a better way to start, that would be less likely to lead to an argument and get a truthful response, would have been to start with something less confronting.

How to Ask Questions the Right Way

Asking questions is like having a conversation. For example, you don’t bump into someone on the street and immediately interrogate them. You usually start with “Hello, how are you?” “How is your family?” “How is life treating you?” You put them at ease by asking questions that show you care about them and are not confrontational.

Socrates knew this. We have reports of conversations he had, such as with a general, who reported one such casual meeting with Socrates. It became apparent that Socrates wanted to question him about his present life-style and the way he lived his life in the past, a topic he was unlikely to discuss.

But Socrates did not start with that. He gradually guided the conversation towards his primary purpose, and as the general reported, “Once he had me trapped, Socrates wouldn’t let me go until he had fully cross-examined me”.

In the current example we are using, your questions might start with simple, innocuous ones, like:

- Why did you choose to live in this area?

- What do you like most about the area?

- What don’t you like about the area?

Which may progress to more poignant questions, such as;

- Have you ever noticed that we seem to have a higher incidence of XYZ disease in the area?

- If you felt the area was unsafe but you were not sure if that was true, what do you think the community should do to put everyone’s mind at rest?

As you can see, we frame these questions in a non-confrontational and non-interrogative style that puts the person at ease and asks sensible questions that encourage them to think without forcing them to think about the issues being raised.

Think of Your Questions as a Daisy Chain

In a daisy chain of questions, the answer to the first question lays the foundation for the second question and answer, with the answer to each of the next questions becoming more obvious and leading the person being questioned to a pre-determined final destination.

In the example above, the answer to the question “If you felt the area was unsafe, but you were not sure if that was true, what do you think the community should do to put everyone’s mind at rest?” will probably be: we should ask the potential polluter to investigate it.

To which you have your prepared follow on question: If you ring the plant manager and ask them, are they polluting the air, the water or the soil, do you believe if they were, they would admit it to you because you ask them?

Answer: Maybe, but probably not.

These questions also lead the listener to think about why the community should take action rather than leave it to individuals, without you having to ask the question. That is how the daisy chain works.

They will probably reach the conclusion you wanted to hear, because only by being united are they capable of achieving a solution, even if that solution reinforces their peace of mind by confirming all is well. But in a worse case, if there is a major problem, they are in a better position to deal with the issue as a united group.

Of course, the destination Socrates wanted to reach was to have his “victim” answer the hard questions he put to them. He did not have any predetermined result he was aiming for. He only wanted the truth so he could better understand what people felt or believed or how they acted versus how they say they would act.

The Socratic Method is powerful for getting to the truth or the nub of a matter, but it is also a powerful tool for helping people to think logically about troublesome issues that they are not comfortable about.

Once the community achieves a solution to an issue that seemed hard to solve at first, they may decide they can address other issues better as a community. This might include issues like child care, which is an issue that families often have to address individually and in competition to each other for limited places.

A community approach to solving common issues could lead to a fundamental shift away from the current conventions that have become embedded in society, such as relying on state or federal government to solve most issues for everyone.

We accept such solutions as the norm and do not question them because they have been around for a long time and may have been the best solution once. As all levels of government find they have more issues to address than the resources needed to solve them, often leaving people feeling frustrated, lonely and “on their own”, it may be time to question these norms.

Some might see this as a shift “back” to the way things were, raising the question, how did we move away from this community approach to living and why?

What do you think?

P.S. I look forward to meeting you through your comments to the articles in this blog. If you would like to write an article as a guest blogger please contact me to discuss your proposed article. Just go to the contact us page and email me.

Best Wishes,

Ric Vatner

shadowintheflame.com